Nick Knotts, Industrial Engineer, The Lawton Standard Company

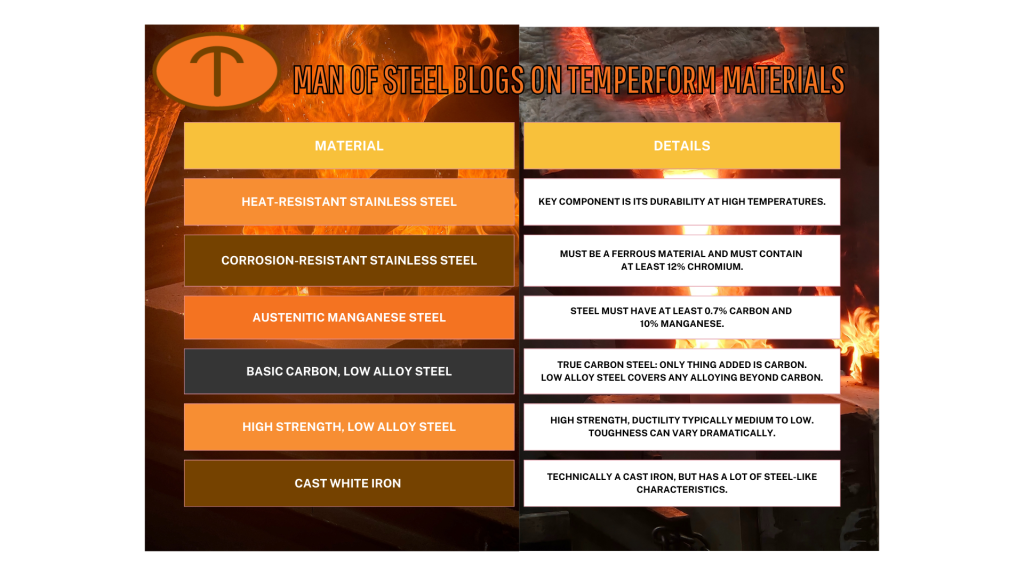

Today, we will be continuing our series of blogs on Temperform Materials. So far, we have talked about Heat Resistant Stainless Steel, Corrosion Resistant Stainless Steel, Austenitic Manganese Steel, Basic Carbon and Low Alloy Steel, and High Strength, Low Alloy Steel. In this blog, we will cover one of the more oddball material categories, White iron. It is a very unique material with some very specific applications. By definition, white iron is technically a cast iron, but it has a lot of steel-like characteristics that often times cast iron does not, and it is used in service more like steel. White iron has some very interesting challenges that accompany it in the casting process that need to be navigated carefully in order to achieve consistent success.

White iron is a material that has some different subsets, the lines between which are rather blurry, and some may argue the lines don’t even exist. To understand how these subsets developed, and why they’re important, we really need to go back to the discovery of white iron and follow the story from there.

The story of white iron starts in the year 1915, when it was discovered that increasing the nickel and chromium content of cast iron produced a highly abrasion-resistant material. It was shortly after this that the term “Ni-Hard” was born, which for a while was the only type of white iron that really existed commercially. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) created a specification for abrasion-resistant cast irons called ASTM A532 in 1993, which covers all of the Ni-Hard alloys. ASTM A532 does not cover any alloys that were not a part of the original Ni-Hard family of alloys.

That being said, Ni-Hard is no longer the only type of white iron, there is now another subset of white iron, which many people are calling “high chrome white iron”. In some ways, the terms “Ni-Hard” and “white iron” and “high chrome white iron” are used interchangeably, but they probably shouldn’t be. I would probably say that high chrome white iron should be a term reserved for any white iron alloy that contains more than 25% chromium. Ni-Hard fairly effectively covers most of the alloys up to 25% chromium (with some exceptions), but many metallurgists will advocate for even higher chromium contents to achieve the most ideal properties, some pushing towards 40%.

Applications and Properties for White Iron

White iron has one application, abrasion-resistant components. The history of the alloy largely led to this, it was never meant to do anything else besides be abrasion resistant, so there are very few concerns about the other mechanical properties. You can think of it like a ½” combination wrench as opposed to an adjustable wrench. The ½” combination wrench is way better than the adjustable wrench for use on ½” components, but you can use the adjustable wrench for a variety of sizes, while on anything other than ½” components, the combination wrench is useless. White iron is just like that ½” combination wrench; other alloys can do the job that it does, but not even close to as successfully as white iron can. However, white iron can only be used for an abrasion-resistant application, otherwise, the material is essentially useless.

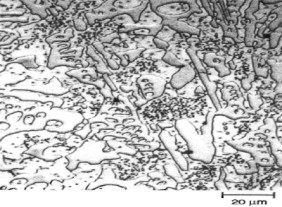

From a mechanical standpoint, one could classify this material as low strength with practically no ductility or toughness. The key physical property with white iron is the surface hardness, which is typically between 450 and 650 Brinell (BHN). The surface hardness is what gives the white iron its abrasion resistant properties. The microstructure of white iron is very different from that of your typical cast gray or ductile iron. In gray iron, a ladle inoculation is used to form graphite flakes with the carbon in the material, a similar process is used in ductile iron that includes a magnesium treatment to form graphite nodules in the material. In the case of white iron, there is no ladle inoculation or treatment, which means that the carbon does not form graphite flakes or nodules. Because the carbon does not form graphite, it instead stabilizes the austenite and forms a lot of cementite, along with some other carbides, which is what makes the material so hard… and so brittle.

Because of this extremely low strength and toughness, white iron absolutely cannot be used in any structural or load-bearing components. It also cannot be used in any components where the casting is receiving impact. This is where the line typically gets drawn between white iron and austenitic manganese steel, which are both often used for abrasion resistant applications. White iron will almost always outperform manganese steel in terms of abrasion resistance, even if the manganese steel is in the work hardened condition. However, there are a couple of situations in which white iron absolutely cannot be used and typically manganese steel is the chosen material. The first is if the casting bears any load or requires any amount of ductility to function, white iron has almost no ductility and very little strength, while manganese steel has high ductility and at least decent strength. The second situation is if the material that is causing the abrasion has any considerable amount of mass to it, or if it is hitting the casting directly instead of running along or over the casting. White iron is extremely brittle and cannot handle any amount of impact while manganese steel is built to handle impact, and work hardens through the impact.

White iron is typically used to make components like wear plates and liners that are designed to handle abrasive material, or are designed to protect other components from abrasive material. There are other types of parts made out of white iron, but those are the most common, due to their direct need to be abrasion resistant.

Castability of White Iron

White iron is another material that is fairly simple to cast in a lot of ways, but also has some unique challenges. The fact that there is no ladle inoculation typically makes melting and pouring it easier than pouring gray or ductile iron by comparison. The chemistry is also much less sensitive to variation when compared to gray or ductile iron.

The first significant challenge with casting white iron is its high sensitivity to hot tears. The sensitivity to hot tears comes from a few different factors, the first is the obvious lack of ductility. As the metal solidifies, the areas that go solid first very rapidly lose ductility as they cool down. If those solid spots are being pulled on by spots that are still liquid, the material is very susceptible to hot tearing. Another reason is due to the low thermal conductivity of white iron when compared to basic carbon steel, which leads to large temperature gradients being able to form in the material. These factors combined are responsible for the increased sensitivity of the material to hot tearing.

The second significant challenge with white iron is the susceptibility of the castings to cracking during shakeout, riser/gating removal, and cleaning. This is due to the same reasons as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the non-existent ductility of the material and the low thermal conductivity, but with the addition of as-cast stresses in the part. I will be the first person to admit, I have seen a lot of white iron castings crack in the cleaning room, mostly because I had a limited understanding of how to handle the castings at the time, and I did not produce a suitable process. However, these failures have made me a better engineer and a better metallurgist, and by learning from those experiences, we have developed a robust process for handling these castings at Temperform that allows us to consistently clean white iron castings without cracking issues.

Among the issues we have faced at Temperform, the first is when it comes to shakeout, if a white iron casting gets dropped from an elevated height, or get struck by a fork truck, it is almost guaranteed to crack. In order to combat this, we are extra careful during the shakeout of white iron castings. Another area where we used to see a lot of white iron castings crack is during cut-off with the abrasive wheel, or during arc-air. The heat applied to the castings during the cut-off/arc-air process often causes the material to expand enough in some areas to cause it to crack. To deal with this, we have been using breaker cores on all of our white iron castings. By using breaker cores, we can take advantage of the brittle nature of the material, which allows us to remove the risers without applying any heat, and remove the risers faster than with a cut-off wheel or an arc rod. White iron is so brittle that we can take off some fairly large risers without having to use a lot of force, so long as the breaker is well designed. The final issue that we have faced is having grinders apply too much force when trying to grind down the pads left over by the breaker cores, which heats up the castings just enough to cause small cracks that can be detected with penetrant testing and will often become larger in heat treatment. The way we deal with this is just by encouraging our grinders to be patient with white iron, taking a little bit of extra time in the grinding room is far better than going fast and causing the casting to go in the scrap pile.

Heat Treatment of White Iron

White iron is not required to be supplied in the heat-treated condition, many grades can often meet the required mechanical properties as-cast. However, that being said, it is typically best for the user and the foundry to do some sort of heat treatment. The type of heat treatment varies based upon the exact chemistry and hardness requirements. At Temperform, all white iron castings receive, at bare minimum, a stress relieve. The stress relieve removes many of the stresses that form as-cast and does not significantly soften the material, which reduces the crack sensitivity of the material while maintaining a high hardness.

If the material is not hard enough as-cast, an austenitize and quench cycle may be performed to harden the material. This austenitize and quench performs hardening in white iron very similarly to how it hardens a carbon or low alloy steel, by transforming the matrix to austenite and then rapidly cooling it to form martensite, which increases the hardness of the material. Some white irons contain some amount of martensite as-cast, but an austenitize and quench will almost always increase the martensite content. Where the process differs significantly from carbon and low alloy steel is that there is no conventional temper that follows the quench, this is because a conventional temper would soften the material too far, which is unacceptable in white iron.

What often follows the quench is a stress relieve, and in my opinion, it is best practice to always do a stress relieve post-quenching with white iron, unless there is absolutely no other way to hit the desired hardness than to skip the stress relieve. The stress relieve slightly reduces the hardness, but it largely reduces how brittle the material is, which makes it a lot easier to handle around the shop, during shipping, and at the customer for installation.

Conclusion

White iron is a material that is another one of those materials in the steel foundry world that is extremely unique and interesting. Tailored to abrasion-resistant applications, it is the gold standard when it comes to materials for wear and abrasion resistance. However, one must exercise caution when choosing white iron as their material for abrasion resistance, because in the wrong application, white iron components will not survive. If you are looking for wear resistant and abrasion resistant castings, but don’t know what material to use, Temperform would be happy to help you select your material! If you already know what you would like, that’s fine too, Temperform would be happy to provide you with a quote for your casting. Reach out to one of our steel experts today to get a quote!