Nick Knotts, Industrial Engineer, The Lawton Standard Company

This blog is another continuation of our series covering the different families of steels that Temperform produces. In our last entry, we talked about Basic Carbon and Low Alloy Steel, which is a subcategory of the broader group of carbon and low alloy steel. This blog will cover the other subcategory of carbon and low alloy steel, that being high strength, low alloy steel. In addition to just high strength, this will also cover the more specialty alloys that are designed for high toughness.

The history of high strength and low alloy steel is largely tied to the history of carbon steel in general, which was covered in the last blog on Basic Carbon and Low Alloy Steel. As with basic carbon and low alloy steel, the primary designation system for these materials is the one adopted by the American Iron and Steel Institute.

Performance and Applications

High Strength, Low Alloy steel’s mechanical properties can be best described as just that… high strength. However, there are other properties that are worth noting too, the ductility is typically medium to low, depending on the exact grade and heat treatment. The toughness of this group of alloys can vary dramatically, again, depending on grade and heat treatment.

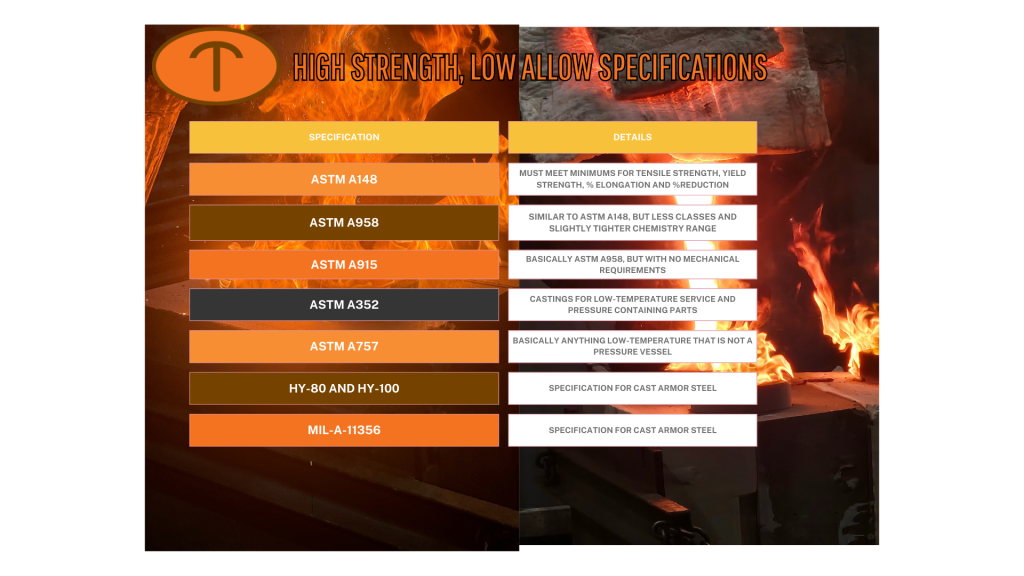

The most common specification for these materials is ASTM A148, which contains grades with ultimate tensile strengths of anywhere from 80ksi to 260ksi. The class labelling convention is the same in ASTM A148 as it is in ASTM A27, which we covered in the previous blog on basic carbon and low alloy steel. The convention is shown below:

Ultimate Tensile Strength (ksi) – Yield Strength (ksi)

Again, these specified values are minimums, there are not maximums or ranges on these classes in ASTM A148. However, unlike ASTM A27, ASTM A148 also contains minimums for the % elongation and the % reduction in area to quantify the ductility. As with the tensile and yield strength, these values are minimum and have no range or specified maximum. In order to certify a casting to a grade, the heat-treated test bar must meet or exceed all the specified minimum mechanical requirements. ASTM A148 also contains an optional supplementary requirement for Charpy impact testing and puts it on the manufacturer and the purchaser to agree upon acceptance criteria.

Two other specifications in this area are ASTM A958 and A915. ASTM A958 is very similar to ASTM A148, however it contains slightly less classes, and also puts a slightly tighter range on the chemistry for certain grades. ASTM A915 is essentially A958, but with no mechanical requirements.

Another arena of specs that should be discussed in this blog are the specifications from ASTM that cover castings for low-temperature service, pressure containing parts, or both. The first two in this lane are ASTM A352, and ASTM A757. ASTM A352 covers steel castings for low-temperature service and for pressure containing parts, ASTM A757 adds onto this saying it is for pressure containing parts and “other applications”, so basically anything low temperature that is not a pressure vessel. These specifications spell out the tensile strength, yield strength, % elongation, % reduction in area, just like ASTM A148 and ASTM A958, but they also add requirements for Charpy impact testing that are built into the specification instead of being a supplementary requirement. With a few exceptions, ASTM A352 and ASTM A757 both spell out the required test temperatures for the Charpy impact test, the minimum average impact values of three test specimens and the minimum impact value for a single test specimen.

Besides the ASTM specifications, which are the most common, there are also a plethora of other specifications out there for high strength, low alloy steel. Among these are the NAVSEA specifications for HY-80 and HY-100, MIL-A-11356, which is a specification for cast armor steel. There are a few various applicable ISO specifications, and others. Many times, with these high strength, low alloy steels, customers will author their own specifications, which sometimes contain additional requirements beyond what is specified by the ASTM specification.

Castability of High Strength, Low Alloy Steel

In the previous blog on basic carbon and low alloy steel, we talked about the challenges posed by oxidation and re-oxidation. All of the challenges with oxidation and re-oxidation that apply to basic carbon and low alloy steel also apply to high strength, low alloy steel. There are a couple of additional challenges with high strength, low alloy steel though that are worth mentioning.

The first challenge is in regard to welding, most of the basic carbon and low alloy steels can receive production welding without any significant amount of pre-heating. With high strength, low alloy steel, this characteristic changes, and a lot of these alloys require pre-heating in order to be welded. Without pre-heating, these materials are prone to cracking during welding for a few different reasons, two of which can be summarized here. The first reason is that large thermal gradients can form in the material as it is welded, causing areas near the weld to become extremely hot, and others to remain cold. This expansion of the metal near the welded area, and then subsequent contraction once welding is finished can cause non-uniform cooling that will crack the material. The second reason is that these higher end low-alloy steels will often form non-tempered martensite as they re-cool from the welding, which is extremely brittle and can crack easily… depending on the situation.

The second large challenge comes in relation to producing castings that are able to meet extremely demanding customer requirements. A lot of these high strength, low alloy steel castings are used in structural applications, pressure containing applications, and other highly demanding applications, otherwise, they would not be using high strength, low alloy steel. These highly demanding applications sometimes carry additional requirements beyond just the standard mechanical requirements. These additional requirements can be things like Charpy impact testing, internal soundness requirements, surface condition requirements, etc. When these additional requirements exist, more considerations must be made up front when designing the casting and rigging system, choosing the charge materials, and setting up the process to produce the material and the casting.

Heat Treatment

The heat treatment of high strength, low alloy steels is something that has been researched extensively in recent years, which has led to a number of advancements in heat treatment to produce continually higher strength and higher toughness steels. Beyond that, development of higher and higher alloyed grades of steel that still technically qualify as “low alloy” have opened up Pandora’s box when it comes to possibilities in heat treatment. There are a ridiculous number of possibilities for heat treating high strength, low alloy steel, so covering all of them in this blog would be impossible, so we will just be covering the more common ones.

As with basic carbon and low alloy steel, the principles of austenitization and homogenization that I covered in that blog apply here also. In these higher strength materials, the large difference comes in terms of the cooling rate and the pre and post heat treatment that surrounds the primary austenitization.

Quench and Temper (QT)

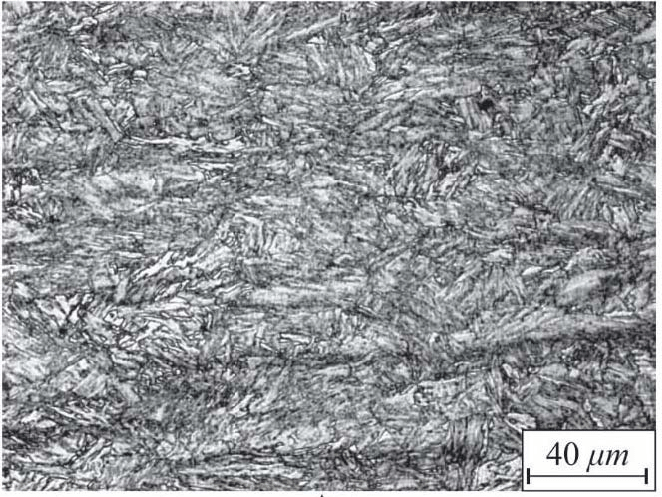

The quench and temper is basically the foundation of all of the heat treatment cycles for high strength steel. No matter how it happens, what happens before/between/after it, the quench and temper is almost always a part of the heat treatment process for high strength, low alloy steel. In a QT cycle, the steel is heated up such that the microstructure fully turns to austenite, typically somewhere in the 1600F-1800F region, and held for approximately one hour per inch of the thickest section of the casting. Following the hold, the steel is immediately transferred from the furnace/oven to a liquid bath where it is “quenched”. The liquid in which the steel is quenched and why that liquid is chosen tends to vary, but the most common liquids that are used are water, oil, and sometimes polymer. In general, water cools the steel the fastest, oil 2nd fastest, and the polymer the slowest, however, all will cool the steel faster than just plain air. Water tends to provide the highest surface hardness, oil the second highest, and then polymer is the lowest. This scale loosely applies to the tensile strength also, but that assumption has been challenged in recent years. When it comes to ductility, polymer typically provides the highest, oil is in the middle and then water is the lowest.

Following quenching, the steel is then tempered. Tempering is done to eliminate the undesirable mechanical properties that are formed during quenching, while also largely retaining the desirable properties that come from quenching. Steel in the as-quenched state, before tempering, is VERY hard, but it is also extremely brittle, which can cause catastrophic failures under even a very small amount of impact. Tempering relieves the stresses formed during quenching and increases the ductility of the material. Though tempering does reduce the hardness of the material, it is a necessary evil to ensure it is not brittle. Tempering temperatures can vary anywhere from as low as 400F to as high as 1200F, depending on what the application is. The hold time for the temper can be as short as 30 minutes, and as long as a couple of hours, depending on the exact situation.

Quenched and tempered low alloy steel usually produces a steel with high strength and hardness. The ductility and toughness can vary a lot based upon the alloy content.

Normalize, Quench and Temper (NQT)

NQT is, in a lot of ways, just a better version of QT, particularly in castings. An NQT cycle is just a QT with a normalization that occurs before the austenitize and quench. This normalization cycle will typically have a hold temperature of 100 degrees Fahrenheit or more than the hold temperature of the austenitization that is done immediately prior to quenching. The goal of this normalization cycle is to heat treat away microsegregation, reform the crystal structure in the metal, relieve many stresses formed in the casting process, and generally make the casting more homogenous before an austenitization. Some work has been done on exploring very high temperature normalizing in order to ensure full homogenization in the casting prior to austenitization, even as high as 2150F, but that practice is still fairly rare in commercial settings.

There are a lot of advantages to using an NQT cycle as opposed to a basic QT. The risk of quench cracking is dramatically reduced when using an NQT cycle as opposed to just a QT cycle, which is something that I have personally learned the hard way. Due to an NQT cycle further reducing microsegregation than a basic QT, NQT will usually produce more uniformity in the mechanical properties throughout the casting. NQT also generally produces material with better toughness and ductility than QT. The tensile strength of the material remains very similar between QT and NQT.

Quench and Double Temper (QTT)/Normalize, Quench and Double Temper (NQTT)

I decided to lump QTT and NQTT together because they are both cycles that contain a double temper. When a second temper is added, it is typically at the same or a lower temperature than the first temper. The idea behind a double temper is to further relieve the stresses formed during the quenching process and increase the ductility and the toughness of the material. In practicality, this does work, but over the years, metallurgists have found better options to achieve this higher toughness and ductility of the material.

There are a lot more specialty heat treatment cycles out there, most of them are designed to meet extremely demanding high strength or high toughness applications, but they are all fairly infrequently used, so I won’t dive into them here.

Conclusion

High strength, low alloy steel is a fascinating material that can handle the most demanding applications when it comes to mechanical strength. When a combination of strength and toughness is needed, high strength, low alloy steel can handle that too if the proper chemical composition and heat treat cycle are chosen. High strength, low alloy steel is one of my personal favorite materials because of the variety of ways one can achieve the desired mechanical properties with different methods, it makes producing the material constantly interesting and challenging. If you need some high strength, low alloy steel castings for the most demanding applications, look no further than Temperform, and reach out to a steel expert today!